Abstract

The aim of this article is to evaluate my underlying beliefs and assumptions about the use of technology to support learning. It takes the form of a series of paragraphs which interweave key learning theories with experiences of digital technology in the classroom towards reflecting on the impact these can have on the growth of pedagogical mindsets. Core approaches range from: Ray Land’s description of threshold concepts, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s flow theory, Biggs and Tang’s ideas on deep and shallow learning, Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development, Kolb’s learning styles and experiential learning cycle and finally considerations around constructive alignment. Through reflecting on these theories I speak of the importance of making the role of technology in the classroom less prescriptive and more goal-oriented, which is something that will help develop learner experiences. However, a core facet of this article is realising that this is not a one way process and demands that teachers expand their own pedagogical mindsets.

Published on 13th March 2020 | Written by Jeremiah Ambrose | Photo by Marius Masalar on Unsplash

Introduction

This article serves as a reflective response to a series of questions asked during the course of my studies on the Postgraduate Certificate in Creative Education (PGCE) at the University for the Creative Arts. The initial assignment occurred on week 12 of the course (18-24 Nov), which focused on technology and accessibility, but also served as a recap for the learning theories covered at this stage in the course. The aim of this article is to expand on this assignment and evaluate my underlying beliefs and assumptions about the use of technology to support learning. It takes the form of a series of paragraphs which interweave key learning theories with experiences of digital technology in the classroom towards reflecting on the impact these can have on the growth of pedagogical mindsets.

To what extent does using digital technology in your teaching constitute a threshold concept for you?

Prior to starting the PGCE I had this vague idea that I needed to make better use of digital technology in the classroom, both in an offline and online context. However, over the course of the first term I have come to realise how naive a thought this was. Previously I framed technology as a useful tool in a pedagogical context, but now I am starting to see its transformative function as something that promotes inclusion in the classroom. This opens up two new key spaces for me that align with Ray Land’s (2017) description of threshold concepts – the first of these is an intellectual space as no longer am I just concerned with turning up and delivering my lectures – I now view my teaching as a constantly evolving process that works in tandem with the use of digital technologies in the classroom. It’s also got me thinking about ways in which student learning experiences can be improved through the use of digital technology (in an accessibility context and beyond). Alongside the PGCE being a threshold concept in itself that is reconfiguring my view on what teaching is – digital technology has also opened up a new emotional space, one where I am being more mindful of experiences outside of my own frame of reference, but also one that is student-centred. It’s also heightened my thoughts on the importance of critical approaches to digital technologies as although they can be pervasive and sinister they also offer the potential to completely reshape how we learn.

When you have used digital technology in your teaching, what aspect of learning were you aiming to enhance? Were you successful? If so, how? If not, why not?

Over the last couple of weeks I have had artist presentations where my year 2 students are given an artist whose work they have to research and then they have to present their findings to the entire class. I noticed after the first session that this group were not very vocal when it came to responding to the presentations and asking questions regarding how this might relate to the practice this coincides with (which was the main aim of these sessions). For this reason I tried using Padlets in the classroom to allow students to write responses and keywords to help generate conversations about each artist, but also look for common threads in their work. I thought this would be a useful document to have, but also the anonymity might at least help me facilitate conversation using student-led ideas – rather than the conversation being purely derived from my own notes. The main aim of this was to enhance collaboration and communication in the classroom. This was useful at first, but descended into chaos when the server was not updating fast enough due to Eduroam being somewhat patchy at certain times of the day. This led to students focusing on the technologies shortcomings, which just added another layer of issues to an already difficult session. Approaching this in future I wouldn’t entirely depend on the live element of the Padlet and have post-its as a backup for the technology failing.

Would you say that you take a ‘deep’ or ‘surface’ approach to using digital technology in your teaching?

In line with the first question I answered for this task I think prior to the PGCE I was using digital technology in my teaching on a surface level. I can blame a lack of time as this is something that we can all relate to, but upon reflection I think it was due to a lack of knowledge around pedagogy. I happily used tools requested of me by the University, such as Blackboard ultra for screen capturing and lecture recording, but at that time I wasn’t equipped to consider how digital technologies can be used to expand student experience, promote inclusion and allow new ways for them to learn. In particular the Chinese cohort that I used to teach at UCL could have benefitted from the live captioning and translation software that I have been researching as part of the final group activity for term one. Although part of an ongoing process I now think I am starting to take a more deep approach to using digital technologies and as I navigate new teaching environments I am constantly asking how could things be improved through the use of technology. Through looking at how Biggs and Tang (2011) visually demarcate the problems with passive student activity and frame deep learning as an active process that involves factors that move away from processes such as rote learning (Image 1) – I started to see a correlation with Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s (1990) ‘flow theory’, in terms of how active high level arousal can be sustained to promote active learning that promotes deeper levels of engagement. Flow theory offers a different mechanism for dynamically adjusting the difficulty, but I think this is something that educators often do instinctually in the classroom and is also something that digital technology can be used to allow students to fluctuate from: describing, explaining, relating, applying and theorising.

Think of an example of when someone has helped you enter your Zone of Proximal Development regarding digital technology. What did you find helpful (and/or unhelpful) about their approach?

Lev Vygotsky defines the Zone of Proximal Development as:

“The distance between the actual development level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers.” (Vygotsky, 1978: 86)

In terms of an example where I found myself entering the ZPD in relation to digital technology the obvious case of this for me was the final project for my M.Sc. For this our group was building a data visualisation software which involved collating data and graphically visualising the difference between male and female registered students at the University since it began. On a technical level this was a massive programming challenge, especially for me as this was a conversion masters and maths and logic had always been a weak point for me. Given that this was almost entirely self-guided I learnt a lot through researching and developing a data visualisation by myself, but I also reached a certain point where I was unable to fix a strange bug so I booked a meeting with my programming tutor to see if he could help troubleshoot. Reflecting back on this there were pros and cons to how he approached this session. Firstly he immediately fixed the problem, which seemed obvious to him, which was great as my project was working as expected, but from a learning point of view I still didn’t entirely understand why I was having the problem in the first place. Thankfully I asked him if he could talk through the logic of the error so I could understand and he then proceeded to abstract the problem and explain each component in detail. Looking back this is probably the moment I learnt the most during this final project as a lot of pieces clicked into place and I started to get a better sense of programming logic and how it works in this context. Through his rigorous process I also got a better sense of how troubleshooting in coding works, which is something that I have continued to build on since this degree. I look back on this with fondness, but it’s also curious where I’d be at if I never probed this teacher further to explain the process, rather than just fixing the problem for me.

How might you use technology to enable your learners to cognitively construct their own understanding of a topic?

The best example of this is a 48hr smartphone challenge that myself and my colleagues collaboratively developed for 1st year students in Film & Digital Art at UCA Farnham. According to Karl Aubrey and Alison Riley’s definition of social constructivism it “refers to the notion that for successful learning to take place any new knowledge encountered needs to be analysed in relation to what learners already know” (2019, p.3). Keeping this in mind and that this challenge was framed as an induction week exercise we decided to use the technology that is most personal and familiar to the students for this exercise – their smartphones. We also made the theme of the work around environment, but kept this open ended enough that it didn’t have to specifically be about issues of the natural environment and students could take this theme and explore it in any way they wanted. The work was a starting point for a dialogue indicative of the journey they are about to go on, but also offered them the opportunity to discuss their interpretation of the task in their presentations, whilst offering a fun and informal format to kick of their studies through a form of active engagement. The outputs of this challenge are documented on our course blog:

https://dfsacourse.blogspot.com/2019/09/48-hour-smartphone-challenge.html

When have you experienced technology being used to positively/negatively reinforce a certain behaviour?

The most obvious case of this is throughout my entire experience of tutoring virtual reality to a cohort of Chinese students at UCL. Given the complexity of the software they were using and the mammoth task of equipping students in a year with the knowledge to create VR work I often had to design tasks in the software for them to engage and understand certain programming processes. However, at times this was problematic as I designed my lessons for students to build on these labs and grow their knowledge over the course of their masters, but some students simply wanted to pass and from a cultural perspective if something wasn’t being graded many of the students would do the bare minimum. How I approached teaching these students reinforced this mentality at times due to time constraints I had to set work to exist outside of the classroom, but I wasn’t allowed to make this carry any weight in terms of credits. Also, many students would use the technology to mirror my projects, but never be willing to expand beyond this, which was limiting and homogenous at times. I struggled with this as it was primarily due to the logistics under which this course was built and poor management. However, some students moved beyond this and were incredibly innovative in terms of how they adapted and used the ideas that I presented to them (which would be my normal expectation at masters level). In this context it would reinforce the willingness these students showed to push the boundaries and experiment, but for others I was always concerned how it negatively reinforced structural issues that I was not in a position to amend.

Think of an example of when you have introduced a new piece of technology into your teaching. What could you learn by using the four stages of Kolb’s cycle of experiential learning to analyse your experience?

Last year I did my first experimental 360 film workshop at UCA Farnham, which involved using a brand new 360 camera that I had not used before and its accompanying software. The workshop was delivered in 4 parts over the course of the month so the goal of each day was to have a concrete experience that both myself and the students could reflect on in the following session. For the students I wanted them to rethink how they approach the idea of cinematography and realise that this allows them to approach things in an entirely new way. Also it allowed me to reflect on the pros and cons of the camera and build these observations into future workshop iterations. As the students reflected on each experience it gave rise to exciting ideas they wanted to explore in their final piece of practice and this entered into active experimentation quite naturally as the students presented me with ideas that I wasn’t even sure was possible with the camera.

Moving through these cycles of experience allowed students to practically engage with the technology, but also conceptually dream of ways to build this into a new cinematic language. Alongside this I had the opportunity to develop approaches to help the students realise these ideas, processes which I could share with them by building on existing knowledge they had of After Effects and Premiere. This module is something that I am constantly updating, but I also think Kolb’s model is perfect for how I visualise it as I hope that each time I deliver it that new technical understandings and practical forms of engagement with the technology will allow students to conceptualise new and exciting ways of harnessing the potential for technology that is still in its infancy.

When have you experienced the constructive alignment of digital technology to help students achieve intended learning outcomes?

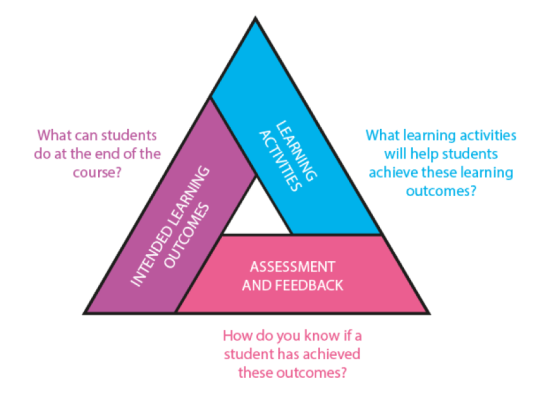

I have experienced this in my own course design of interactive 360 film and unity labs at UCL. The process would start by defining the intended learning outcomes, which would involve varying degrees of practical and theoretical understandings of these fields. After this the assessment and teaching activities would be designed to help students achieve those outcomes.

The above diagram (Image 4) illustrates how these processes are interrelated. This is vital as a roadmap for why the student is using the particular technology they are using, but also in terms of having a goal for how the technology can be used in a less prescriptive manner and more inline with Kolb’s cycle of experiential learning towards a student-led experience that promotes cognitive constructivism realised through threshold concepts that are aligned with a growth mindset that not only leads to new and unexpected outcomes but also evolves the learner in the process.

Conclusion

Over the course of this article I have reflected on a range of learning theories and their relationships with digital technologies. This has allowed me to engage deeply with my own teaching experiences and start to consider the impact various technologies have on teaching. At the end of the previous paragraph I spoke of the importance of making the role of technology in the classroom less prescriptive and more goal-oriented, which is something that will help develop learner experiences. However, this is not a one way process and demands that teachers expand their own pedagogical mindsets. This not only highlights the importance of learning theories, but also the manner in which these are put into dialog with the technologies that enter our classrooms. Such conversations are vital given the ubiquitous nature of digital technologies and the symbiotic relationships these have with contemporary teaching environments.

Jeremiah Ambrose works in the areas of digital art, media futures and experimental practice, and is currently Y2 Leader and Lecturer on the BA Film & Digital Art at UCA Farnham.

Jeremiah’s research interests are practice-based, with a focus on iterative practical experimentation and theoretical considerations in the areas of VR, 360 Film/Photography, Immersive/Interactive Media Art, Digital Culture, Expanded Cinema, Experimental Film, and Cybernetics.

References

Aubrey, K. and Riley, A. (2019) Understanding & Using Educational Theories (2nd edition). London: Sage Publications

Biggs, J. and Tang, C. (2011) Teaching according to how students learn. In Biggs, J. and Tang, C. (eds.) Teaching for Quality at University: What the Student Does. (4th edition). Open University Press, 16-33

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990) Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper Perennial

Evidence Based Education. (2017) Ray Land: Threshold Concepts. 1st December 2017. [ONLINE]. (Accessed: 5 November 2018)

McLeod, S. (2017). Kolb’s learning styles and experiential learning cycles. [ONLINE] (Accessed 26 November 2019)

NTU (2012) Outcomes Based Teaching and Learning. [ONLINE] (Accessed 26 November 2019)

Vyotsky, L. (1978) Mind in Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

One Reply to “”