Abstract

Inclusive of socio-economic disadvantage, young people from a variety of backgrounds and characteristics are underrepresented in Higher Education (HE) in England. While attainment at secondary school strongly predicts whether a young person might go into HE, it is also difficult to disentangle attainment at Key Stages from the cyclical influence of prior disadvantage. Creative arts have the potential to expand HE progression opportunities for a number of underrepresented groups, including those from underrepresented and deprived geographic areas. Arts-based education initiatives can encourage HE participation among students from disadvantaged backgrounds through changing attitudes and developing transferable skills. This article presents the preliminary evaluation of a suite of creative arts outreach activities in the Kent and Medway region in England as part of Phase 1 of the Office for Student’s Uni Connect programme. Through a theory of change perspective, mixed methods are used to explore changes in short-term attitudinal outcomes associated with the creative outreach activities. Results show that participation in creative outreach coincided with perceived increases in self-efficacy, intentions of applying to HE, and perceptions of the importance of creative arts in society. Feedback from interviews and focus groups helped to illustrate underlying factors that contributed to facilitating attitudinal change.

Published on 16th Marcg 2020 | Written by Daniel Goodwin, Emma Bunyard, Holly Rogers and Marie Connolly | Photo by Anna Earl on Unsplash

Introduction

This article explores the potential for creative arts-based outreach initiatives to reduce participation gaps in Higher Education (HE). Based on geographic analysis of local areas in England, there is a 31 percentage point gap between those most and least likely to participate in HE (OfS, 2019). A young person’s prior attainment at GCSE is consistently shown to strongly predict their likelihood of entering HE (Chowdry et. al., 2013, Wiseman et. al., 2017). However, accounting for prior attainment, some gaps associated with socio-economic background remain (Chowdry et. al., 2013). Alongside attainment, the type of school or college that students attend and social background may influence chances of applying to and entering HE (Barkat, 2019) – whilst acknowledging the reflexivity of disadvantage impacting on attainment from an early age (Raffo, 2007).

In England and Wales, there has been a widening gap in HE participation rates in favour of females since the 1990s, although, much of this is explained by similar disparity in GCSE attainment (Broecke & Hamed, 2008). Participation varies by ethnicity and, in general, minority ethnic groups are more likely to go to university than their White British counterparts, albeit with considerable variation across the different ethnic groups (Crawford, 2015). This analysis holds when prior attainment and socio-economic factors are controlled for, however, results are different for the most selective institutions where some Black ethnic identities are the most underrepresented.

HE Participation and employment in the Arts

Rewind some decades and ‘arts school’ was a likely educational route following post-compulsory schooling for those from more working class backgrounds or with lower-level qualifications (Banks & Oakley, 2015). Presently, however, students studying arts courses in HE in the UK are more likely to be from relatively advantaged social backgrounds (Brook, et. al., 2018). Moreover, the creative HE population is less diverse then the general HE population with higher proportions identifying as White ethnicities (over 80%) and female (over 60%; UniversitiesUK, 2018). In terms of social mobility, employment in creative occupations is described as increasingly overrepresented by those from more privileged social origins (Brook, et. al., 2018).

In spite of this context, or perhaps because of it, creative arts has the potential to expand on the HE progression opportunities for underrepresented groups, particularly for white males and ethnic minorities from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds and from the geographic areas with low HE participation. This potential for widening participation can be seen in London where, for example, one fifth of males from the lowest participation local areas (POLAR) studying in HE are doing creative arts and design subjects (Alberts & Atherton, 2016). These data should also be viewed cautiously as, HE participation rates are, on average, higher in London, which also has relatively few of the lowest participation local areas in England (HEFCE, 2014).

The role of creative arts outreach

There are a number of roles that creative arts outreach can play. Firstly, arts-based education may help encourage HE participation among students from lower socio-economic backgrounds through provoking attitudinal change (through the self-reflective, meaning-making and expressive characteristics of arts), supporting the development of transferable skills, and increasing creativity (Felton et. al. 2016). Moreover, co-curricular creative arts programs in disadvantaged schools may, in the shorter-term, help to build social connections and increase awareness of post-secondary education (Vichie, 2017), whilst, in the longer-term, help to build social and cultural capital and widen HE participation (Geagea, et. al., 2019). Providing young people with creative opportunities is all the more relevant, as arts participation in English schools has been impacted in recent years by policy influencing the curriculum at Key Stage 4, in particular, due to the introduction of the English Baccalaureate, which diminished the importance of arts in the curriculum (Johnes, 2017; Last, 2017).

Arts Award (Arts Council England) is an initiative where young people can gain arts qualifications through both in curriculum and extra curriculum programmes. Thus, within the context of the marginalisation of arts within the school curriculum, Arts Award can play a role in supporting young people’s educational agency, attainment and progression in the arts (Robinson, et. al., 2019; Hollingworth et. al. 2016; Smith, 2013). Research relating to the Arts Award programme has identified the following perceived benefits from participating in extra-curricular creative activities (Hollingworth et. al. 2016): building personal development and life skills (including confidence, leadership and organisational skills); supporting choice of subjects and successful applications; gaining accreditation; nurturing understanding of routes to employment in the creative and cultural sector; and encouraging independent learning, communication and networking skills. Additionally, participating in extra-curricular arts activities can have a more marked impact on those with less ‘cultural capital’ (Hollingworth et. al. 2016) and may support improvements in informal, softer skills, which are fostered through creative learning (Robinson, et. al., 2019).

Outlining a theory of change

This article is concerned with understanding the role of creative arts-based outreach in contributing towards closing participation gaps in HE (generally and more specifically in creative arts and design), with reference to the Kent and Medway regions of England, UK. This article describes an outline Theory of Change approach to evidencing the contribution outreach interventions can make to outcomes (Figure 1), whilst recognising broader complexities and challenges with attributing causation (Barkat, 2019). The Theory of Change approach is grounded in a social realist perspective, which acknowledges that “different structural and cultural factors and processes can combine in ways that enable and/or constrain young people’s educational reflexivity and agency and their ensuing educational engagement and attainment” (Raffo, 2015). The approach seeks to identify underlying mechanisms that might help explain how outcomes were caused and the influence of context (Marchal, et. al. 2012).

This work adopts a more ‘small steps’ approach (Harrison & Waller, 2017), with interventions focused on personal development. Creative arts curriculum has the potential to engage and enhance educational outcomes (Scholes & Nagel 2012) and while there is some evidence of the wider educational benefits of creative subjects, there is a lack of evidence on the impact of arts on academic attainment in other subject areas (See & Kokotsaki, 2016). Interventions that young people took part in intended to influence young people to enhance their transferable skills including resilience, communication, teamwork and independence. Implementation of creative pedagogies was encouraged through the following interventions:

-

- Non-residential holiday clubs (four days campus during school half-terms)

- Residential Summer Schools (four days on-campus during the Summer Term)

- Creative workshops taking place in their school settings

- Visits to a university campus

- Six week Saturday Clubs

- Creative Masterclasses

- Alternative curriculum provisions

- After school clubs

Change and influence was intended through the provision of opportunities to:

-

- Spend a significant amount of time (3 or 4 days) experiencing a creative subject within a specialist arts environment

- Access specialist arts facilities and equipment

- Work at their own pace and experiment with ideas both independently and collaboratively, with creative input from tutors acting as ‘role models’ and facilitators

- Experience the HE environment and interact with HE staff, most notably creative academics, outreach staff and current student ambassadors

- Experience wider arts and culture through associated off-site trips and visits to local galleries, museums and studios

- Build relationships with artists, tutors, practitioners and peers

- Have fun and learn new creative techniques and skills – both practical and evaluative

As discussed by Anthony (2019), the smaller steps approach considers interventions aiming to improve shorter-term attitudinal outcomes as a way of helping to support attainment raising. Moreover, as there are small gaps in HE progression based on socio-economic background once KS4 is controlled for (Chowdry et. al., 2013), there are opportunities to help close this part of the gap and make marginal gains through supporting applications and nurturing understanding of routes to employment in the creative and cultural sector; and encouraging independent learning, communication and networking skills (Hollingworth et. al. 2016). Through exploring the data, the analysis seeks to understand to what extent a theoretical link can be traced through participation in creative arts outreach, any increased sense of self-efficacy or self-concept in creative arts or perceived development of soft skills and the young participants’ intentions to progress into HE. This summary paper is concerned with the initial, short-term outcomes of the Theory of Change and does not include data to look at intermediate outcomes nor HE progression, however, implications are discussed.

Methods

Participants aged 13-19 (in Years 9-13 in school or doing Level 3 in a FEC) took part in creative arts activities as part of Phase 1 of the Office for Student’s Uni Connect programme (previously NCOP) in Kent and Medway between January 2017 and July 2019. Overall, over 5,500 young people participated in creative outreach (Table 1) coordinated by the University for the Creative Arts (UCA) which included Arts Award activity programmes and alternative curriculum led by the Arts Education Exchange (ArtsEdEx). Participants’ details were collected at outreach events following the requirements of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Data Protection Act (2018) and using public task as the legal basis for processing personal data.

Creative outreach activities included:

-

- Creative workshops exploring creative arts, business and technology disciplines

- ‘Create Calm’ workshops promoting positive wellbeing through creativity

- Creative Trip and Workshop Packages

- Thrive Youth: Creative Careers Conferences

- Assemblies, Talks and Presentations

- Portfolio Review Sessions

- HE Fairs and Options Events

- Arts Award opportunities at Discover, Bronze, Silver and Gold levels

- Creative Masterclasses

- YouCreate – a submission based Creative Competition

- Creative Holiday Clubs

- Residential Summer Schools (Image 1)

- Creative Saturday Clubs

- Mentoring

The majority took part whilst in Year 11 (30%), followed by Year 10 (25%), Year 12 (19%), Year 9 (17%) and Year 13 (9%). The average age was 16.

Referenced to the schools where the outreach participants were enrolled, the creative outreach cohort of participants was proportionally higher for females and higher for Uni Connect target participants (Table 1). Two purposively selected data samples consisted of outreach participants who had: (1) completed pre- and post-intervention surveys and (2) participated in an interview or focus group. Interview participants, who were from two disadvantaged schools in Thanet with high proportions of disadvantaged pupils and below average attainment, were invited to take part when they completed their programmes of activities. Similarly, focus groups were recruited by contact activity participants. Survey data were collected at outreach events using public task as the legal basis and informed consent was obtained from all interviewees and focus group participants. These samples were not intended to be representative of the school populations for the schools of the young participants, nor more broadly for all schools in Kent and Medway. The two data samples were bias towards those from low HE participation areas (Uni Connect target wards) and bias towards female participants. The average age for data sample 1 was 16 year with 64% in pre-16 year groups. For data sample 2, the average age was 15.5 years with 58% in pre-16 year groups.

The creative interventions delivered by UCA included more intensive, self-sign up activities including seasonal schools (Half Term, Easter and Summer Schools) and Saturday clubs. On the other hand, less intensive activities, such as creative workshops, were delivered by UCA to selected groups of young people in their schools during normal school hours and many young people participated in a combination of activities. The average hours of outreach received by an individual was 29.6 hrs (+/- 23.9). This analysis did not seek to evaluate outcomes for individual activities but rather, the participation in any combination of creative outreach initiatives as part of the Uni Connect programme in Kent and Medway during Phase 1.

For data sample 1 (pre and post-intervention surveys with repeated measures, n=127), the responses to Likert-type statements were coded (strongly agree = 5, agree = 4, don’t agree or disagree = 3, disagree = 2, strongly disagree = 1) and multi-item constructs were aggregated for the analysis. Repeated measures were used to measure attitudinal change as short-term outcomes for: Educational aspirations (3 items) self-efficacy (8 items), self-concept in creative arts (7 items), the likelihood of apply to HE (single question item), intentions of participating in the creative arts in the future (4 items), and the societal importance of creative arts (2 items). Using the pre-intervention baseline survey data to assessing the reliability of multi-item measures, Cronbach alpha values of >0.70 indicated reliability of measures, in that, items were measuring similar response patterns (Taber, 2016). Using SPSS (v25), the data (excluding missing values) were explored through paired sample t-tests and then through segmentation analysis using independent sample t-tests to explore outcomes measures in terms of the following independent variables (difference in differences): gender, age, parental experience of HE, geographic indicator of disadvantage (Index of Multiple Deprivation, IMD), attainment at GCSE (self-reported target grades for pre-16 participants and achieved grades for post-16 participants). The analysis was guided by the question: Is there any evidence of attitudinal change, did any sub-groups benefit more (or less) and to what extent can any changes be attributed to participation in the creative arts outreach?

Data sample 2 (qualitative data gathered through interviews with ArtsEdEx project participants, n=17, and focus groups with Arts Award participants, n=7) was thematically analysed to explore the young people’s perceptions and experiences of creative outreach. The approach used was an inductive, data-driven thematic analysis and followed methods outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). The thematic analysis included the exploration of underlying mechanisms facilitating attitudinal change, as described by the participants. This analysis was guided by the question: in what ways could the experiences of the young people help to explain any changes in short-term outcomes? Interviews and focus groups were recorded (audio), anonymised and transcribed, loaded into NVivo and thematically analysed with the participants’ responses being coded based on outcomes they perceived and underlying mechanism that may have facilitated changes in attitudes or behaviours.

Whilst the above methods are capable of exploring the experiences of the young participants, there are methodological biases and limitations. These include social desirability and acquiescence bias associated with self-reported data alongside the awareness of being evaluated that can lead to unrepresentative results (Harrison et. al. 2018). Moreover, there was selection bias where participants who have benefited from the activity may be more likely to provide data. As such, the results were not generalizable beyond the sample used in the analysis.

Results

Repeated measure surveys

For all repeated survey measures of dependent variables, the mean values of the post-intervention responses were higher than the pre-intervention responses. Three of the increases in means could be said to be statistically significant (paired samples t-test): Self-Efficacy, Likelihood of Applying to HE and the Importance of Arts in Society, with small effect sizes[1] (Table 2). Therefore, there was a concurrence of outreach participation with improvements in the attitudinal measures. However, a number of caveats are necessary, firstly that, in the absence of any counterfactual measures, it is not possible to say whether these differences might have been detected regardless of any participation in creative outreach activities. Secondly, the self-reported nature of the data comes with a number of methodological biases and limitations, as already discussed.

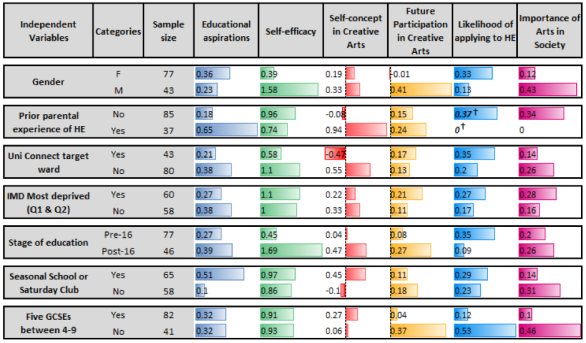

The difference in differences were examined for five independent variables: Gender; Prior parental experience of HE; Level of geographic deprivation; Stage of education (pre or post-16); Type of activity; and Level of attainment (self-reported predicted or achieved GCSEs depending on age). The results showed that whilst there were differences in the change in scores for the outcome measures, for example self-efficacy increased more for males than for females, only one difference was statistically significant (Table 3). The likelihood of applying to HE in the future increased more for those with no prior parental experience of HE.

Table 3 Summary of mean change in dependent variables segmented by independent variables. †Difference between two categories significant at p<0.05

Thematic analysis

Thematic analysis of transcribed interview and focus group data identified salient outcomes and changes that participants described they had experienced during their time completing Arts Award activities along with descriptions of some of the mechanisms that may have helped drive the changes they experienced (Figure 2). The mechanisms related in different ways to the outcomes that participants described and many of the outcomes could be qualitatively linked (e.g. circular correlation) such that one change related to another (and vice versa). As an example of the linkage between the outcomes, learning new creative skills may have helped to build students’ confidence and as confidence grew, they were also able to explore their new skills in more detail. The following feedback illustrates how one Arts Award participant felt their confidence was improved at school through taking part in extra-curricular activity:

“I would say it’s definitely boosted my confidence with my arts work at school. To start with I wasn’t so confident with some different medias but now since coming to UCA I feel more confident in all different medias I use now.” (R.B)

The participants made connections between the underlying mechanisms and the outcomes, for example, having the time to work at their own pace helped with learning new skills, building relationships, improving self-awareness and formulating next steps, as illustrated in Image 2. The following quote illustrates how experimentation and freedom aided in a participant’s perceived development:

“They help you to be more creative and experiment with new skills. We have lots of freedom to develop independently, but the workshops provide a good starting point.” (R.21)

The thematic analysis results indicated that the outcomes participation in creative arts outreach supported were: learning new creative skills; building relationships and trust; developing self-awareness; and formulating next steps in terms of creative practice and education. The interview data helped to illustrate underlying factors that contributed to facilitating change and included: being able to work at their own pace; having the freedom to explore ideas and experiment; being supported and influenced by the creative practitioners tutoring on the course (particularly through role-modelling); collaborating and working together; experiencing different educational and arts settings (such as visiting the University for the Creative Arts); and through having fun.

Through self-reported survey data, positive increases were observed for repeated measure attitudinal constructs for Self-Efficacy, Likelihood of Applying to HE and the Importance of Arts in Society. The positive increases were observed in concurrence with activity participation and there was evidence of a greater degree of change for those whose parents did not have any experience of HE (perhaps unsurprising, as participants whose parents had prior experience of HE were more likely to say they would apply prior to taking part in an outreach activity). Thus, this finding adds to the proposition that creative outreach may, in the longer-term, help to build social and cultural capital, raise expectations and widen HE participation, particularly for those from more disadvantaged backgrounds and in disadvantaged schools (Geagea, et. al., 2019). In the absence of any counterfactual measures, however, it is not possible to say whether these changes might have been detected regardless of participating in the creative arts outreach. There was no specific evidence that the participation in creative outreach would encourage HE participation among students from low socio-economic backgrounds more than those more relatively advantaged backgrounds. However, there was evidence that, regardless of socio-economic background, participation could help to provoke attitudinal change and support the development of transferrable skills, thus supporting previous research findings (for example see Felton et. al. 2016).

The thematic results emerged as similar to previous research findings relating to Arts Award participation (Hollingworth et. al. 2016; Robinson et. al., 2019) and highlighted a number of benefits to taking part in Arts Award, including: The development of creative arts skills and critical thinking skills; Perceived improvements in self-esteem, confidence, self-efficacy, and motivation in school; How the development of arts projects and portfolios had helped participants think about specific interests, future study interests and careers they would like to pursue. Overall, the qualitative data indicated that participation in creative arts outreach had helped the young people develop more clarity in terms of navigating their future educational and life choices, making future plans and developing steps to get there, again, in a similar vein to previous research (for example see Robinson, et. al., 2019). In summary, the rich qualitative data collected from young people, many attending disadvantaged schools and being from disadvantaged local areas, helped illustrate the role of creative outreach through providing access to social and cultural capital (Geagea, et. al., 2019; Vichie, 2017) and contributing towards positive shifts in educational expectations and perceptions of HE.

Conclusions and Recommendations

This article has presented preliminary analysis of a suite of creative arts outreach activities coordinated by the University for the Creative Arts in the Kent and Medway region in England undertaken as part of the OfS’s Uni Connect programme. Through an outline theory of change perspective, mixed methods were used to explore changes in short term, attitudinal outcomes associated with interventions that ultimately aimed to help increase progression into HE.

Whilst the mixed methods were useful for exploring the experiences of the participants, there were methodological limitations including those associated with self-reported data, the lack of counterfactual outcome measures and the non-generalisability beyond the small sample of participants. As a next step, more robust analysis is necessary to improve the quality of evidence on the impact of arts activities (See & Kokotsaki, 2016) and for outreach activities in the widening participation sector (Crawford, 2017). Nestled within a theory of change framework, further evaluation should look to analyse attainment outcomes at Key Stage 4 for participants of pre-16 outreach activities. Given the strong correlation between Key Stage 4 and future progression to HE, this will provide a reliable proxy for final HE participation. Data on eventual progression into HE will also be sought once the creative outreach participants are old enough to apply. Moreover, further levels of intersectionality should be explored where larger samples sizes are available. Through linking the various short, medium and longer-term outcomes, further analysis will help to uncover the broader contribution of creative arts outreach towards supporting young people in navigating educational and career choices and, ultimately, helping to close participation gaps in HE.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Office for Students Uni Connect programme for funding the continuing work & development of creative arts outreach in Kent and Medway through the Kent and Medway Collaborative Outreach Programme (KaMCOP). We would like to acknowledge the Higher Education Access Tracker (HEAT) for the provision of school and FEC data. The authors also wish to acknowledge the work of Ollie Briggs at the Arts Education Exchange that has contributed to this article and the University of Kent, specifically Lydia Hall for conducting the Focus Groups. Finally, the authors would like to thank Dr Anna Anthony of HEAT for her input into the development of the manuscript.

Daniel is the Monitoring and Evaluation Officer for KaMCOP at the University of Kent. He is responsible for evaluation strategy, theory of change development and data analytics. With a doctorate in the sociology of water management and a masters in sustainable architecture, Daniel is now immersed in widening participation and is animated by contributing to the evidence base on closing gaps in educational disadvantage.

Emma Bunyard is the Collaborative Outreach Manager for the UCA KaMCOP Team. Emma has worked in educational settings in Kent for many years and is a prominent figure in the Kent and Medway outreach sector. A strong believer in the impact of creative outreach for the development of young people, Emma is a champion for Creative Careers and pathways.

Holly Rogers is the Collaborative Outreach Officer and Arts Award Lead for the UCA KaMCOP Team. With a background in Fine Art, Holly values the importance of creative activities and cultural experiences to develop and enhance young people’s skill sets. This has been particularly prevalent in Holly’s work delivering Arts Award which aims to raise young people’s aspirations and opportunities to progress to Higher Education.

Marie Connolly is the Collaborative Outreach Officer for the UCA KaMCOP Team. Within her role, Marie works with multiple schools in Kent and Medway championing creative disciplines and pathways. With a background in Sociology, Marie has a passion for reducing inequality in education.

Together, Holly, Emma and Marie are part of the KaMCOP team based at University for the Creative Arts. Part of an Office for Students (OfS)-funded national Uni Connect programme, KaMCOP aims to promote social mobility by improving access to Higher Education for young people from underrepresented backgrounds.

References

Anthony, A., (2019) ‘What works’ and ‘what makes sense’ in Widening Participation: an investigation into the potential of university-led outreach to raise attainment. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent.

Barkat, S., (2019) Evaluating the impact of the Academic Enrichment Programme on widening access to selective universities: Application of the Theory of Change framework. British Educational Research Journal, 45(6), pp.1160-1185.

Baker, Z., (2019) Reflexivity, structure and agency: using reflexivity to understand Further Education students’ Higher Education decision-making and choices, British Journal of Sociology of Education, 40(1), 1-16, DOI: 10.1080/01425692.2018.1483820

Banks, M., and Oakley, K., (2016) The dance goes on forever? Art schools, class and UK higher education, International Journal of Cultural Policy, 22(1), 41-57, DOI:10.1080/10286632.2015.1101082

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. DOI:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Broecke, S. and Hamed, J., (2008) Gender gaps in higher education participation: An analysis of the relationship between prior attainment and young participation by gender, socio-economic class and ethnicity. Department for Innovation, Universities & Skills. Research Report 08 14.

Brook, O., O’Brien, D. and Taylor, M., (2018). There was no golden age: social mobility into cultural and creative occupations. SocArXiv. DOI:10.31235/osf.io/7njy3.

Chowdry, H., Crawford, C., Dearden, L., Goodman, A. and Vignoles, A., (2013) Widening participation in higher education: analysis using linked administrative data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 176(2), pp.431-457.

Raffo, C., Forbes, C., & Thomson, S., (2015) Ecologies of educational reflexivity and agency – a different way of thinking about equitable educational policies and practices for England and beyond?, International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(11), 1126-1142, DOI: 10.1080/13603116.2015.1044201

Crawford, C., Dytham, S., and Naylor, R. (2017) The Evaluation of the Impact of Outreach. Proposed Standards of Evaluation Practice and Associated Guidance. The Sutton Trust, DfE, OFFA and University of Warrick.

Crawford, C. and Greaves, E. (2015) Socio-economic, ethnic and gender differences in HE participation. BIS Research Paper 186 London BIS.

Felton, E., Vichie, K., & Moore, E., (2016) Widening participation creatively: creative arts education for social inclusion, Higher Education Research & Development, 35(3), 447-460, DOI: 10.1080/07294360.2015.1107881

Geagea, A., Vernon, L., & MacCallum, J., (2019) Creative arts outreach initiatives in schools: effects on university expectations and discussions about university with important socialisers, Higher Education Research & Development, 38(2), 250-265, DOI:10.1080/07294360.2018.1529025

Harrison, N., Vigurs, K., Crockford, J., Colin, M., Squire, R. and Clark, L., (2018) Evaluation of outreach interventions for under 16 year olds: Tools and guidance for higher education providers. UWE Bristol, The University of Sheffield & Sheffield Hallam University.

Harrison, N. and Waller, R., (2017) Evaluating outreach activities: overcoming challenges through a realist ‘small steps’ approach. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 21(2-3), pp.81-87.

HEFCE, (2014) Further information on POLAR3 An analysis of geography, disadvantage and entrants to Higher Education. Higher Education Funding Council for England. Available at: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/19292/1/HEFCE2014_01.pdf

Johnes, R., (2017) Entry to arts subjects at Key Stage 4. Education Policy Institute.

Last, J., (2017) A crisis in the creative arts in the UK? HEPI Policy Note 2 September 2017. Higher Education Policy Institute.

Marchal, B., van Belle, S., van Olmen, J., Hoerée, T. and Kegels, G., (2012) Is realist evaluation keeping its promise? A review of published empirical studies in the field of health systems research. Evaluation, 18(2), pp.192-212.

Office for Students (2019) Participation Performance Measures. Available at: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/about/measures-of-our-success/participation-performance-measures/gap-in-participation-between-most-and-least-represented-groups/ accessed 29/11/2019

Raffo, C., Dyson, A., Gunter, H., Hall, D., Jones, L. and Kalambouka, A., (2007) Education and poverty. A critical review of theory, policy and practice. Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Robinson, Y., Paraskevopoulou, A. and Hollingworth, S., (2019) Developing ‘active citizens’: Arts Award, creativity and impact. British Educational Research Journal. 45(6), pp.1203-1219.

Scholes, L. and Nagel, M.C., (2012) Engaging the creative arts to meet the needs of twenty-first-century boys. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 16(10), pp.969-984.

See, B.H. and Kokotsaki, D., (2016) Impact of arts education on children’s learning and wider outcomes. Review of Education, 4(3), pp.234-262.

Smith, D., (2013) An independent report for the Welsh Government into Arts in Education in the Schools of Wales. Welsh Government.

Taber, K.S., (2018) The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education, 48(6), pp.1273-1296.

UniversitiesUK, (2018) Patterns and trends in UK Higher Education 2018. UniversitiesUK. Available at: https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/facts-and-stats/data-and-analysis/Documents/patterns-and-trends-in-uk-higher-education-2018.pdf

Vichie, K., (2017) Building creative connections: An analysis of a creative arts widening participation program. In: Current and Emerging Themes in Global Access to Post-Secondary Education (GAPS), pp.101-111. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Wiseman, J., Davies, E., Duggal, S., Bowes, L., Moreton, R., Robinson, S., Nathwani, T., Birking, G., Thomas, L. and Roberts, J., (2017) Understanding the Changing Gaps in Higher Education Participation in Different Regions in England. Department for Education.

[1] Effect size calculated using Cohen’s d = (Mean2 –Mean1)/√((St.Dev12 + St.Dev22)/2): 0.2 to 0.5 = small effect, 0.5 to 0.8 = medium effect, 0.8 and higher = large effect.

One Reply to “”